Turkey is set to hold elections on May 14. Country’s current president and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) leader Tayyip Erdoğan has been using the “election economy,” making populist promises for attracting votes in this critical turn. Turkish economy, on the other hand, is more fragile to handle such promises.

In the pre-election period, it is customary for the ruling parties to turn on the populist taps and “revitalize” the economy. However, in order to do this, you need funding to flow when you turn on the faucet. If the resources have dried up, it is possible to enter the May 14 elections with a very different picture.

So, what is that picture?

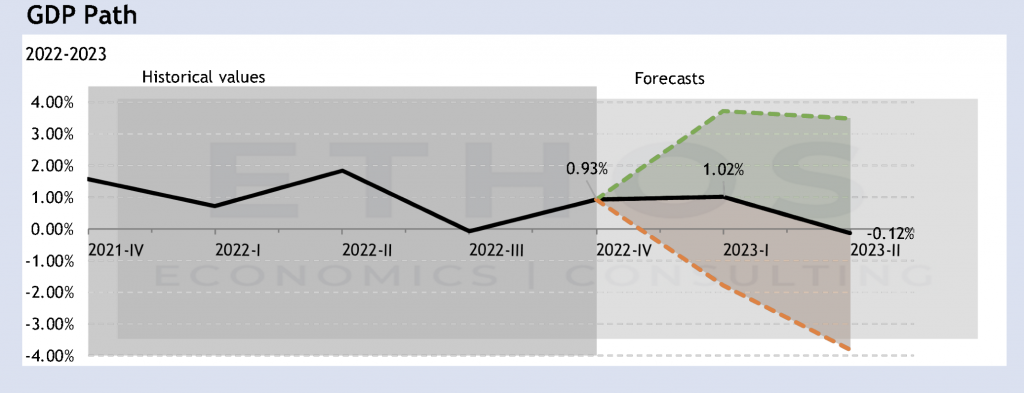

The figure shows our quarterly growth forecasts with Cem Çakmaklı and Sevcan Yeşiltaş from Koç University. In the light of the latest data, we observe the following dynamics:

It seems that the resources are drying up and there is no room for a new doping that we have seen in the past, in every slowdown.

We are facing a rather dim growth outlook right before the elections, which would not be the intended outcome of government policies. What went wrong? Shouldn’t low interest rates be supposed to bring higher investment, growth, and employment?

The answer to this question is clear: It is true that interest rates are the cost of borrowing. But in order to lower the policy rate and stimulate growth, you need to lower interest rates without fueling inflation.

So, let us look for an answer to this question:

What happens if inflation increases when you lower the policy rate?

What is the net impact? Let’s look at the data.

Turkey’s Deposit Rates Surpass Commercial Lending Rates. Graphic: Twitter/Selva Baziki @SelvaBaziki

The figure is from the presentation I gave at the Second Economic Congress of the Second Century, March 15-21, 2023 in İzmir, titled “Common Misconceptions on the Turkish Economy”. Following periods when interest rates are kept low and inflation and exchange rates are out of control (red line), investment growth (blue column) declines.

A few messages can be drawn from this relationship:

Did the dynamics that slow down the economy after an increase in inflation not exist in the past, but have come into play now? If inflation suppresses growth, how come we grew 5.6 percent last year? These effects were present in the past, but when the short-term benefits of interest rate cuts were exhausted and their side effects began to kick in, a new round of easings were introduced.

When inflation increased and reduced purchasing power, another round of interest rate cuts was introduced to stimulate consumption.

If the low-interest rate environment increased the demand for foreign currency, the demand was curbed with the exchange rate protected deposit instrument, the cost of which was borne by the public sector (and estimated to be 180 billion TL). If that was not enough, the Central Bank’s foreign exchange reserves were sold (Bloomberg’s Selva Baziki calculates that this figure has exceeded $128 billion since December 2021). When none of that was sufficient, this time they tried to control the demand for foreign currency by tightening credit standards.

At this point, we have come full circle. We started this journey with the aim of lowering interest rates and increasing bank loans to promote growth. Yet at the end of the road, we reached tightening in credit and a slowdown in growth. What we are left with is a rather low but pretty unfunctional policy rate and the resources depleted for this purpose.

In Turkish politics, the threat of imprisonment has reached CHP leader Özgür Özel. Presidential decrees…

The Cyprus issue has remained stuck in conceptual traps for decades, unable to move beyond…

It is understood that the meeting on June 29 between MİT President İbrahim Kalın and…

After five years, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had the opportunity to meet face-to-face again with…

Iranian women have been standing tall for years, not just against the regime, but also…

The U.S. Struck Iran at Israel’s Request. The U.S. launched B-2 heavy bombers from Whiteman…