The dollar borrowing interest rates are at vigorish levels. The BRSA decision does not seem to hold the demand for dollars, and we do not even want to think about what new decisions would be.

After a two-day delay, the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency (BRSA) announced the rationale and the implementation methods for its Decision numbered 10250 (‘Decision’ from now on), taken on June 24 and caused great controversy; including about loans and rates. The statement made on June 26 sets out the reasoning for the Decision.

Trying to understand the Decision

The rationale is as follows: “…it has been observed that some companies, even though they do not have foreign currency debt or foreign currency liabilities, and even have an excess foreign currency position, purchase foreign currency using TL loans and hold foreign currency positions… In this respect, to strengthen financial stability, a macro-prudential measure is deemed necessary to ensure that the loans work effectively and that the loans are used for their intended purpose by using resources in more efficient and productive areas … The Decision has been taken.“

It is understood that the aim is to end the actions of companies that have taken loans in liras and then converted those liras into foreign currency. In other words, decisions are taken to prevent a hike in the demand for foreign currency and thus an upward pressure on the exchange rate through this channel.

What if the exchange rate did not move upwards?

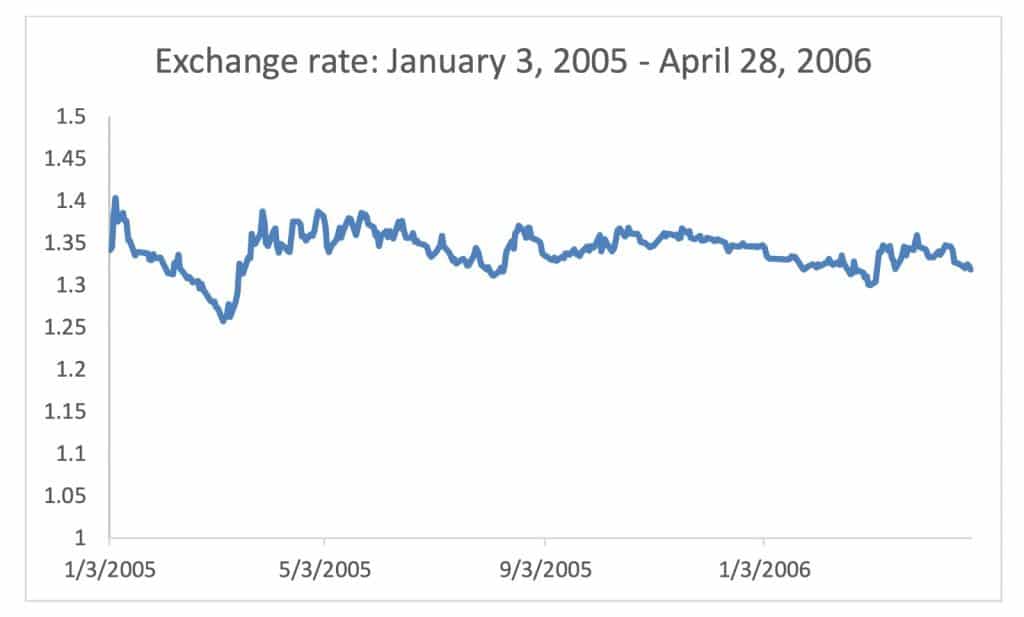

So, why do these companies borrow in liras and convert them into foreign currency? Let me rephrase the question: If the exchange rate moved as in the figure, would those companies take the action that the BRSA is complaining about?

The figure shows the movement of the dollar/lira exchange rate over the sixteen months from 2005 to May 2006. The average exchange rate was 1.34 liras per one dollar in this period; the highest value was 1.40, and the lowest value was 1.26. In other words, an exchange rate follows a horizontal course that can be considered stable.

In such a period, a company would be ‘unwise‘ to incur interest costs in liras, borrow money, buy foreign currency with that debt, and carry that currency as an asset on its balance sheet for a while because the company does not get a return that is worth the effort at the end of that period. Also, it pays interest on the loan it gets; moreover, it does not need that foreign currency to perform its activities.

Rush to get cheap loans

If a company behaves as stated in the reasoning of the Decision, a critical reason is that the exchange rates are constantly increasing, and at the same time, it is very cheap to borrow in liras. The company might need that currency in the future. If it expects the exchange rate would take a very high value when required, and if it can find cheap resources, why not buy that currency?

On the contrary, even if the company would need foreign currency in the future, it would not take this action if the cost of borrowing in liras were high enough. Therefore, there would be no need for the Decision.

Inaccurately decided interest rates

It has been announced that demand for Income-Indexed Bond (GES), with a maturity of six months, is at 6.6 billion liras. The interest rate of this bond is slightly higher than 23 percent, well above its alternative six-month deposit rate, which is around 18 percent.

Under normal circumstances, 23 percent versus 18 percent alternative should be an opportunity not to be missed. Nonetheless, when inflation is 74 percent, neither 18 percent nor 23 percent means anything. When the expected inflation for the next six months is 65 percent, it would be ineffective even if offered a 50 percent return, let alone these rates.

Is it just deposit interest rates? Even though the cost has indirectly been increased with succeeding decisions in recent weeks, loans in liras are still very cut-rate.

BRSA Decision and foreign currency demand

It is not only about “those companies.” As the interest rate is inaccurately set, no one desires to deposit money in liras. The most effective alternative is holding financial assets in foreign currency. Besides, there is no need to buy foreign currency bonds or the like; holding foreign currency itself means holding a financial asset in foreign currency. Result: Increasing demand for foreign currency by citizens.

Of course, the demand for a foreign currency does not rise just for savings, and foreign debt payments are also due.

Overdue external debts

As of April, the amount of external debt due in a year is 182 billion dollars which is an amount that would not be a problem for a large economy like Turkey under normal conditions. Moreover, a significant part of it is commercial loans taken for import and export activities, and it is possible to get those loans again (‘rolling’ existing debt) without a problem.

Subtract business loans and other easily redeemable debts from this amount. Let us assume that 40-50 billion dollars are left. Under normal conditions, it is very likely to borrow this amount again and pay the matured debt. “Under normal conditions,” that is.

Who borrows at this cost?

Nonetheless, our dollar-denominated borrowing rate has jumped to a “vigorish“ rate since the applied economic policy has dramatically increased our risk. Lenders add that risk premium on the return they consider normal (risk-free).

For example, if the Treasury currently borrows in dollars from abroad, it will pay around a 10 percent interest rate. Some borrowers may not want to repay their foreign debt by borrowing again at a rate like this.

Therefore, a portion of 40-50 billion dollars should be paid from domestic resources, another factor that rises the domestic foreign exchange demand and puts upward pressure on the exchange rate. Add to this the financing need arising from the current account deficit, which reached 21 billion dollars in the first four months of the year and is expected to continue to increase in the upcoming period.

Is the Decision a shot in the arm?

Unfortunately not. It is about only one of the consequences of the significant economic policy mistakes made one after another. It is both ‘only‘ one and ‘consequence.’

The main reason that has led to this result still stands. Moreover, this Decision also associates some ideas; it recalls the question of “what if ‘others‘ come next.” New ones can follow the Decision, and I do not even want to think about what “those new decisions“ might be. What is the use of inciting uneasiness?