Behlül Özkan

In April 1986, bombings were carried out to passenger buses in Syria and a Latakia-Aleppo train in Syria. Newspapers in Turkey reported that dozens of people had been killed during the attack. According to the Syrian state television, the 5 people who organized the attack got arrested at the Al Farouk hotel in Aleppo on May 9. Two of the suspects were Turkish citizens: the two cousins, Mustafa and Mehmet Albayrak, who lived in the Bohşin village of Hatay, near the Syrian border. According to the Syrian television, the suspects had confessed to carrying out the attacks, using the explosives that they had brought to Syria from Iraq via Turkey. This incident soon found an echo in global media. According to the New York Times, the organization behind the attacks was the Muslim Brotherhood.

Moreover, three of the Arab suspects were from Hama, the center of the 1982 uprising, where thousands of people were killed by the forces of Hafez Al-Assad led Baath regime. The striking point here was that the New York Times wrote that the Muslim Brotherhood had an “operation center” in Hatay. Upon this, Damascus hurriedly sent Brigadier General Garib from the Syrian Ministry of Interior to Ankara, for consultations. However, the incidents didn’t die down. On May 16, news of a bombing in the Bohşin village where the two Turkish suspects came from, carried out by someone coming from Syria this time, were reflected in the Turkish press. While there were no casualties in the attack, the governor of Hatay dismissed the headman on the village because of “negligence” — was a relative of the two Turkish defendants in the attacks in Syria and carried the same surname: Hasan Albayrak.

This extremely complex and dramatic series of incidents, all tied together in a tangle, soon entered the agenda of Turkey’s parliament. Minister of Internal Affairs Yıldırım Akbulut responded, only months later, on October 1986, to Hatay MP Murat Sökmenoğlu’s question about the two citizens who were captured in Syria and “given the image of terrorists”. He said that “No ideological activities of the mentioned people were encountered before or after September 12 [1980 military coup], nor has any relation with terrorist organizations within our country been detected.” The case was thus closed for Ankara. A year after the bomb attacks, Syria announced that the attackers were executed in August 1987, but the Albayrak cousins’ names were not mentioned among those executed. Damascus covered up the matter.

Serious claims, yet hard to prove

In January 1993, weekly news magazine 2000’e Doğru (“To the 2000s”), known to get its news from “deep” sources, reported that the Turkish intelligence and security units have been backing the Muslim Brotherhood in response to Syria’s support for the PKK — the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party. To quote a “revolutionary” who spoke to the publication: “As the PKK developed, Turkey’s interest in this organization [the Muslim Brotherhood] increased. Hatay’s Reyhanlı and Yayladağlı border gates were opened to them. It later turned out that the explosions of the passenger buses in Syria in 1986, killing dozens of people, was carried out by the two Turkish brothers, members of the Muslim Brotherhood, and that it all happened with the knowledge of Turkey’s National Intelligence Service (MIT). The Muslim Brotherhood members inform with their radio transmitters as they approach the Turkish border. Turkish patrols at the border inform their side that friendly troops are arriving and that no fire be opened. Turkish officials welcome the Muslim Brotherhood at the border and send those who came for military training off to the training troops in the Turkish provinces of Hatay, Kayseri, Konya, and Amasya.”

There are three important points to this long excerpt: 1) Turkey’s foreign policy of putting the Muslim Brotherhood at the core of the action against Syria, and arming the opposition within Syria to overthrow its regime, which we’re familiar with from 2011, had been implemented in a similar way in the 1980s. 2) 1986 coincides with the period where the so-called “Kemalist” army, which supposedly had not compromised “secularism”, had fueled full-blown Turkish-Islamic synthesis. So, supporting the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood, one of the fundamentalist movements of the Middle East, did not disturb the Turkish generals of the time all that much. 3) The 2000’e Doğru publication highlights that it was after 1984, when the Syria-backed PKK’s armed actions began, that Turkey used the Muslim Brotherhood against Damascus. However, my findings suggest that during the Hama uprising of 1982 and even before that, Turkey was at the very least turning a blind eye to the Muslim Brotherhood. On the other hand, it’s a fact that Abdullah Öcalan, had fled to Syria in 1979, a year after founding the PKK and coordinated all armed attacks in Turkey from his headquarters in Syria and Lebanon’s Syria-controlled Bekaa valley.

Let’s get back now to the Albayrak cousins who went from Hatay’s village of Bohşin to Syria and allegedly carried out bombings. I haven’t been able to find a single mention of the Albayrak cousins after the 1993 news piece in 2000’e Doğru. We could presume them dead, considering the bad conditions of the Syrian prisons and the fact that the Arabs they got arrested with were executed. Indeed, no news from the Albayraks until 2009. But in the year 2009, where Bashar Al-Assad [President of Syria after his father Hafez al-Assad’s death] was referred to as “my dear brother Assad,” President Abdullah Gül wrote him a letter about Albayrak cousins. Turkish state didn’t forget about the Albayraks, whom everyone else had forgotten about, and wanted them back. And sit tight: after 23 years, Mehmet and Mustafa Albayrak returned to Turkey in May 2009 as a result of Gül’s letter. Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu visited the Albayraks at their home and told them that they were imprisoned for 23 years “due to a misunderstanding.. Is this convincing to you?

Hama 1982 – Eruh 1984

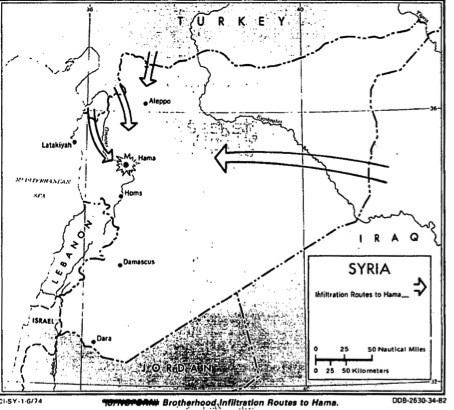

According to the academic studies in Turkey, the problems between Ankara and Damascus stem from Syria’s backing the PKK since the 1980s. The avoided question, however, is the following: what kind of policy did Ankara pursue in the 1982 Hama uprising two years before the Syrian-backed PKK began its armed campaign against Turkey with the 1984 raid on the Şemdinli and Eruh towns near the Iraqi border? The most striking document on this issue is the 1982 report prepared by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency immediately after the Hama Uprising. According to the report, about 300-400 Muslim Brotherhood militants joined the Hama uprising; they had infiltrated Syria mostly from Iraq and, “to a lesser extent”, from Turkey. Some of the information on the uprising, in the report, comes from “the [Muslim] Brotherhood sources in Ankara.” What’s even more striking is the map published in the report showing the routes through which the Muslim Brotherhood infiltrated Syria. According to this map, the militants have infiltrated Syria through Turkey from three points: Kilis, Reyhanlı, Yayladağ. So, Turkey used the same routes and border gates in the Syrian civil war in 2011 as it did in the 1982 Hama uprising.

A General Staff “Internal Threats” report prepared on June 2, 1980, right before the September 12 military coup, accused Syria of supporting “Kurdish activities.” However, according to this report, “the Alevi Ba’ath government in Syria had been put in a difficult situation due to the activities of the Muslim Brotherhood organization established by Sunni Arabs.” It’s remarkable to find the predominant sectarian point of view towards Syria after 2011 had been already present in the same form on the General Staff report of 1980. Clearly, Turkish generals thought that the Assad government couldn’t get out of this difficult situation and Ankara took action upon that. And it’s clear that the establishment in Ankara turned a blind eye to Muslim Brotherhood activities carried out via Turkey. However, the question we’re still yet to answer is, whether Turkey went even further than turning a blind eye to the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood since the beginning of the 1980s and whether it supported them. If so, then how?

Turkish journalists, who visited Damascus in the 1980s had a persistent question to the Syrian statesmen they interviewed: why did Damascus support the PKK? In return, they typically would listen to complaints from the Syrians about Ankara’s tolerant attitude towards the Muslim Brotherhood. Soner Yalçın’s book “Erbakan” has a striking testimony from a Motherland Party (ANAP) minister on the Turkey-Muslim Brotherhood relations: “The CIA-MOSSAD-MİT supported Ihvan against Assad. Assad has had many complaints. MİT was especially in it in 1981. So much so that Assad began to suspect Turkey for everything that happened in Syria. He warned Turkey countless times. Although, later, he did take his revenge from Turkey by supporting the PKK.” According to this statement, Turkey’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood is not a reaction to Syria’s support of the PKK. It seems quite the opposite.

If we consider the close relationship between the Syrian intelligence Al-Mukhabarat and Öcalan after he fled to Syria in the Summer of 1979 and the contacts between the PKK and the secret Armenian armed organization ASALA, and some Palestinian armed groups, and Damascus, the picture becomes even more complicated.

Which came first, the chicken or the egg? Did Syria first support the PKK, or was it Turkey that backed the Muslim Brotherhood? It’s hard to answer. Another question we cannot answer is how Tel Aviv and Washington intervened in the Ankara-Muslim Brotherhood equation if they were at all involved. Syria was the country that opposed the most to the Camp David order in the Middle East after 1979. Furthermore, the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood, with US support, played an important role in Afghan jihad against the Soviet Union. So, it wouldn’t be surprising if Israel and the U.S. had entered the equation at some point.

Same trap after 30 years

From the 1980s on, the Muslim Brotherhood’s presence in Turkey under the supervision of Turkish intelligence and security units in Yalova, Iskenderun, and Mersin, and that they were being trained, appeared in the Turkish press. Prominent journalist Saygı Öztürk announced from the daily Hürriyet’s headline on October 20, 1992, that the Muslim Brotherhood had made an offer to the MİT to kill PKK leader Öcalan in Syria, back in 1987 (which did not take place).

Given that Turkey has got a serious state structure, one could reason that someone, somewhere would be aware of how much trouble the policies against Damascus carried out through the Muslim Brotherhood had caused a blowback for Ankara. The information that I, as an academic, have obtained entirely from open sources, all point to the tragedy of the 1980s being brought back to the stage on a much larger scale after 2011. Forming conquest troops from dissimilar fundamentalist groups, naming armed groups after Ottoman Sultans, claiming to have established a national army by bringing together some ringleaders… However, this time, Turkey faces much more serious consequences compared to the tragedy staged in the 1980s: millions of refugees, a terrible destruction in Syria, the largest terror attacks in Turkey’s history and the emergence of political and military structures at Turkey’s border, which will jeopardize Turkey’s national security for years to come…

NOTE: This article has been published in the 62nd issue of the Journal of International Relations, in English, as a much wider and more comprehensive academic article.