A bunch of Dutch youths, gathered in the midst of the Netherlands, are playing and singing Anatolian pop. Could this be? Where did that come from? When you put aside any cynical reflex to jump into big and mighty conclusions like Identity Crisis, 21st Century Schizoid Man or Global Village Idiot Blues and lend them an ear in good faith, you encounter first-class music and interpretation. It seems that in this day and age, we need to revisit those history and geography books from days of old, and even to rewrite them.

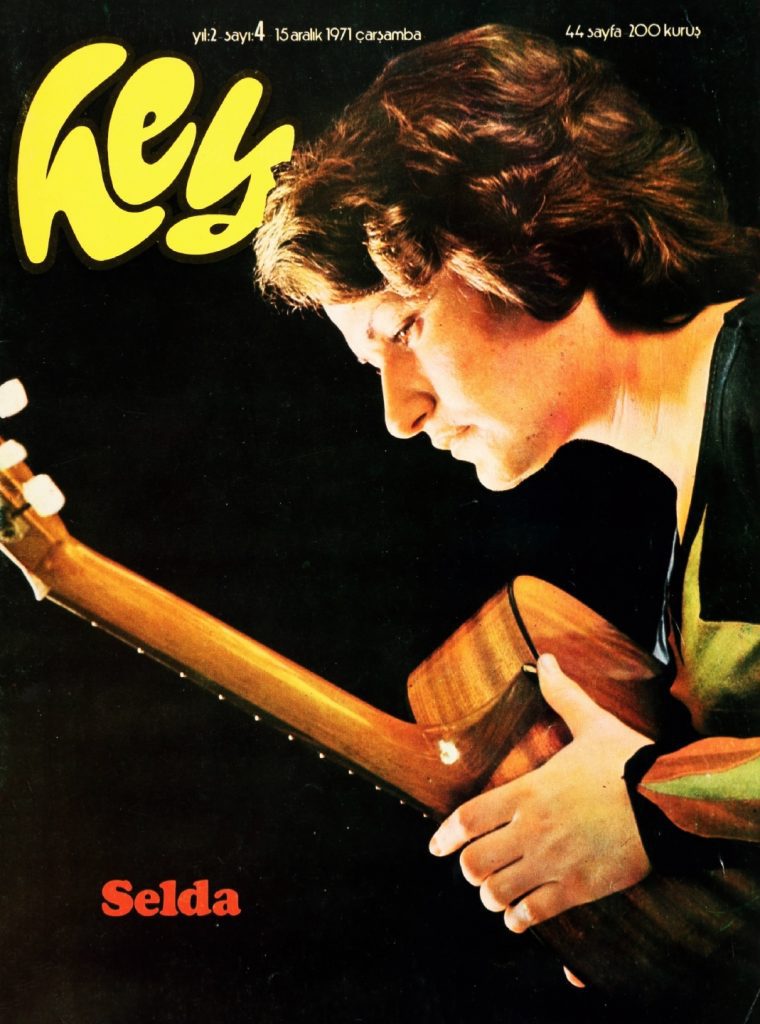

I’m talking about the band called Altın Gün (“Gold Day”; or “Golden Day”). It’s all the doing of bass-guitarist and DJ Jasper Verhulst. Before founding Altın Gün band, Verhulst spent many years in the band Moss, and as part of Jacco Gardner’s orchestral accompaniment. This intriguing musician, passionate about the psychedelic sounds of Third World music of the 60s and 70s, first comes across the music of Selda Bağcan when her old records were discovered and got issued by the European companies in the 2000s. Around the same time, he discovers songs from compilation albums like “Turkish Freakout” and “Love, Peace & Poetry”. These also tend towards the Turkish psychedelic music of 40-50 years ago. He gets further in his journey of discovery when he accompanies Jacco Gardner for his Istanbul concert in 2015. Verhulst snatches that opportunity to get about the record shops in Istanbul, collecting old Turkish records.

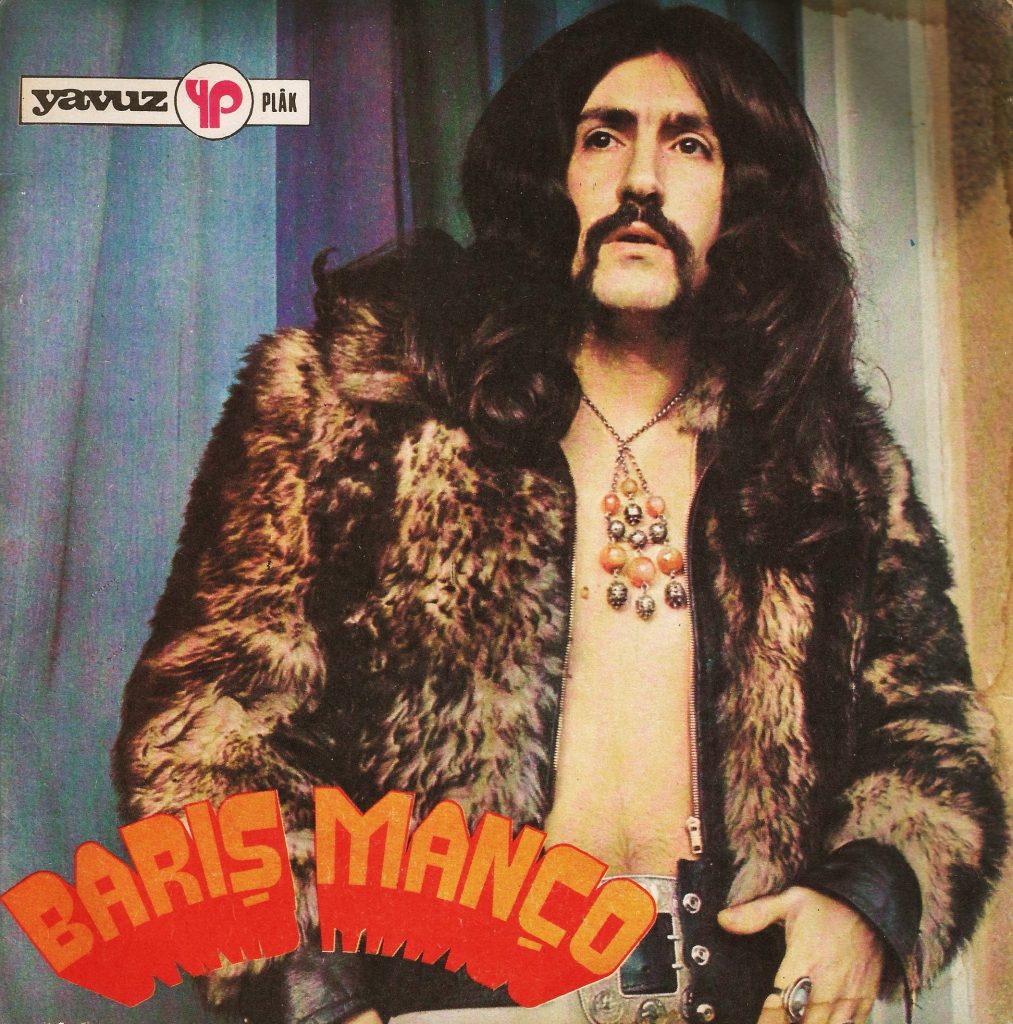

Barış Manço on the cover of his Nazar Eyle single (1974)

According to recent statistics, 400.000 people originally from Turkey live in the Netherlands. But instead of infiltrating this closed-off community within his country, Verhulst chooses to tap into the opportunities that the internet presents. There’s no doubt he has good taste in music. I yielded when I saw such on-point choices as Barış Manço’s “Binboğanın Kızı” (“Binboğa’s Maiden” — 1971) and Selçuk Alagöz’s “Malabadi Köprüsü” (“Malabadi Bridge” — 1975) on his Spotify playlist. Because in terms of sound construction, I have always taken my hat off to those two songs, which are still under-appreciated even in today’s Turkey.

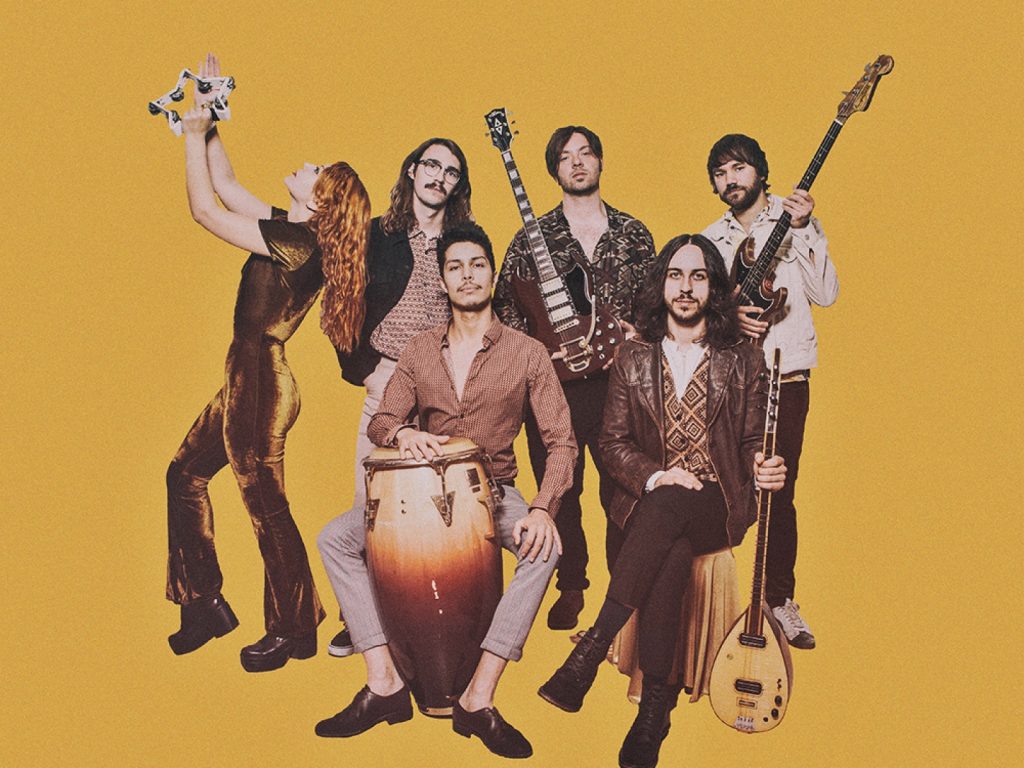

Verhulst completes his band comprising thus far two Dutch and one English musicians with two Turkish musicians who responded to his Facebook announcement: they also become the group’s singers. One of them is bağlama player Erdinç Ecevit Yıldız, who comes from a working class family living in the Netherlands. The other is a former resident of Kadıköy, Istanbul, who came to the Netherlands to expand her future opportunities in music: Merve Daşdemir. Altın Gün’s primary goal is to re-interpret the Turkish standards which had, so far, gotten neither a passport nor a visa into the Western world before and taking them on a world tour.

And as a matter of fact, upon their first meeting, the band rehearse “Malabadi Köprüsü”. I would have liked to witness the very first day that this murderous, feudal love lament, set on a bridge in Diyarbakır, first resonated in the calm and quiet Vondelpark.

Roots and fruits

Anatolian pop (or Anatolian rock) blossomed in the mid-60s in Turkey and became mainstream in a short while. As seasoned orchestral musicians blended local motifs with jazz and bossa nova, young Turkish beatniks wedded Turkish folk songs to the music of the Beatles and their successors. This urban youth had welcomed Western influences with open arms. But they were now drawn to the impoverished Anatolian provinces’ ancient culture, and in a sense, paying them homage. This was also a “return to the roots” while also, simultaneously, the declaration that they were “opening up to the world”. The circumstances were favorable: the Beatles were global citizens first and foremost and their Liverpudlian identity came second. The Turkish youth embraced the message of the Beatles as readily as their peers in African countries, Mexico, Brazil, and Greece. On the other hand, the economic rural flight had already amassed the country folk into the big city and the cultures had begun to merge. Popular rural novels and films were also endorsing this fusion in music.

Turkey’s great dream of the time was to have a Turkish song be heard in the world. As newspapers overflowed with false news that the Beatles, Tom Jones, Ray Charles, and Charles Aznavour were running after Turkish songs, Turkish Anatolian pop musicians were trying to beat a path to the gates of Europe. The short-lived success of the band Moğollar in France, and the songs by the band Beyaz Kelebekler that made it into the Dutch music charts were both exceptions. (It must be added that the influx of workers from Turkey to Germany, France and the Netherlands from the 60s onwards has managed to carry neither a Turkish musical star nor a popular tune across Europe).

Turkish record collectors’ secret objective is to go the Netherlands to forage second-hand record shops and hit the jackpot: Beyaz Kelebekler band’s Dutch-issued vintage 45 rpm single records. This is not an easy job at all. But those who walk into the Concerto record store in 2017 to get their hands on Beyaz Kelebekler but were greeted with Altın Gün played full blast inside the store, were certainly lucky. As soon as their 45 rpm single record came out in 2017 with the songs “Goca Dünya” (“Big Ol’ World”) and “Kırşehir’in Gülleri” (The Roses of Kırşehir”), the band found fame. Their 2018 album “On” and “Gece” (“Night”) which came right after, paved their way into many prestigious music festivals and a Grammy nomination. So Altın Gün’s name was added to the ever-growing list of Turkish musicians that made their names heard in the global press, such as Selda Bağcan, Baba Zula and Gaye Su Akyol.

Big ol’ world

Even though I did find the sound and interpretation compelling when I first listened to their song “Goca Dünya”, I have to admit that I still didn’t care a lot for them. This tune, written and composed by legendary arabesque singer Orhan Gencebay, was covered by many musicians with the verse (“Dünya döner, değirmendir / İnsan, içinde çavdardır” (“the world turns as a mill / and a human’s but a piece of rye in it”) for years. The word “rye”, which has a provincial ring to it, was a small but significant addendum of Abdullah Nail Bayşu, the very person who had introduced Gencebay into the music world. However, this significative addition to the verse must have irked Gencebay over the years, for in the 1990s, he chose to omit the “rye” metaphor and replaced it with “a human’s but a soul” — which took away its originality a great deal. So here I must reproach: Altın Gün mustn’t have sacrificed the “rye”, mustn’t have broken the spell, and mustn’t have fallen into the same trap as Gencebay.

To be truthful, I didn’t like the band’s name either and haven’t encountered a single soul who did so far. It turns out that one day, Jasper Verhulst was on Google Translate (probably looking for the term “Golden age”) and was presented with “Gold Day”; thus the band was given this impractical name that doesn’t translate well in Turkish and even sounds rather raucous. But it’s too late now. Alas, we have to live with this internet accident.

A merry manifesto

I read in various interviews that the group members don’t wish to convey any political messages through their music and that they only aim to create a groove that works, that entertains and gets people to dance. I fully understand their position. It is, of course, unwarranted to put on their shoulders the burden of a political responsibility that they can’t carry. But I’m guessing that there must be some people in their audience who feel the need to have at least a minute amount of knowledge, for context.

Perhaps Europeans don’t know it yet, but even children in Turkey know that there is more to Anatolian pop than love songs and wedding music performed with electric guitars. This music has been political since birth. A great percentage of the socially-charged songs made between 1964-79 was initially composed by folk poets who have had a massive influence on Anatolian pop and Anatolian pop artists. This interaction was ruptured and then transformed after 1980, where a military coup took place, and then continued well into our day.

The main locomotive of Anatolian pop is the melodies of Alevi bards. Alevis correspond to at least 20{4a62a0b61d095f9fa64ff0aeb2e5f07472fcd403e64dbe9b2a0b309ae33c1dfd} of the Turkish population and represent heterodox religious beliefs. Their history is full of massacres and injustice. They have not been seen much within the voter base of the right-wing parties that have been in power in Turkey for many years. Despite this, the humanist, egalitarian lyrics of Alevi bards such as Aşık Veysel, Neşet Ertaş, and even the leftist Aşık Mahzuni managed to make their way into the collective values of the people of Turkey.

Neşet Ertaş’s song, covered by Altın Gün, asks “tatlı dile, güler yüze doyulur mu?” (“could you ever get enough of sweet talk and smiles?”). And Altın Gün makes music that sweet-talks and smiles, just like the song. We live in a time where the effects of a painful workers’ migration are still an open wound, and where discrimination and racism are on the rise amid the current migration crisis. Striving to bring the music of Anatolia, and even, more broadly speaking, of the Balkans and the Middle East to the various audiences across the world, from Europe to the U.S., sure looks like a cheerful, merry manifesto. And that’s why, to me, it feels no different than a sheer political act.