“President Erdoğan is adamant that low-interest rate policies will continue. I am worried that this policy path has grave risks for the economy, and if we do not pivot, those risks could manifest themselves very soon.”

Before the second round of presidential elections on May 28, President Tayyip Erdoğan told CNN International that if elected, he would continue to cut interest rates following his unorthodox belief that “high interest rates cause high inflation” and that “he had already started to see positive results.”

We all wish for a better tomorrow and an investment-friendly environment. We all wish for our children to live in prosperity.

If only rate cuts would stimulate investment. If it were that easy, wouldn’t the rest of the world follow our lead and consider rate cuts to lower inflation and guarantee a prosperous future?

Who would want interest rates to rise, the appetite for investment to decline, and the pie to shrink? Why did over ninety central banks hike rates throughout 2022? Was it out of ignorance or treason? And why do their governments support these central banks?

How come the heads of these central banks are not sacked?

There is no such world

The answer is very simple: A world where you can perpetually stimulate the economy by lowering the policy rate does not exist. Maybe in the short run. But if you don’t take inflationary pressures into account, this policy will explode, yielding a much higher cost. Today’s gains will imply higher losses for tomorrow.

Once rate cuts start to trigger inflationary pressures, you cannot lower the market interest rate even if you lower the policy rate. The longer you insist on your mistake, the higher will be the risks and vulnerabilities, which will further increase market interest rates.

The domestic currency will depreciate. In other words, the very costs of production that you try to reduce via rate cuts end up increasing and contracting the economy.

The pressure on the exchange rates and market interest rates can be perceived as warning signals from the economy’s self-correcting mechanism to fix your mistakes. If you have a basic understanding of the textbook, you would have already seen that erroneous path in the first place because the long-run costs are higher than the short-run benefits. That is exactly why so many countries approached inflation with rate hikes rather than rate cuts.

Better to minimize your losses

Suppose you haven’t read the textbook or you did not find it convincing. And suppose you continue to cut interest rates at the cost of inflation and hope that both inflation and market interest rates will fall. Occasionally, deviations from the textbook do yield positive results. Yet such visionary breakthroughs are rare, and when they do occur, they end up in the textbooks as success stories. The economic theory is reshaped in light of these findings. However, more often than not, deviations from the textbook only end up confirming that the theory was correct in the first place. In such instances, you end up in the same textbook as a box for “what happens if you deviate from orthodox policy?”.

The foreign press is watching the Turkish economic experiment with great interest. We on the other hand are living in this experiment. We pay for the economic hemorrhage with an erosion in purchasing power, an unemployment rate that does not fall below 10 percent, a deteriorating income distribution, and heavy costs that are transferred to future generations. What is worse is that the extent of the economic damage is largely masked by populist subsidies, transfers, and regulations. Yet the question is, what will happen when the resources that are rapidly depleting our national wealth dry up?

Regulation in, regulation out

As the resources that are channeled to offset the pressures on market interest rates and exchange rates are dwindling, the methods employed to exert financial repression get more and more strict. The hundreds of regulations that have been introduced since the beginning of the year continue in an increasing and haphazard manner in the run-up to the second round of the elections. Some regulations are introduced one day and withdrawn the next.

These actions do not give the impression that the policymakers are confident in their decisions and know what they are doing. If that wasn’t the case, the targets of the New Economic Program would have been met by now, or at least approached within a margin of error. Yet the data shows that this is far from being the case.

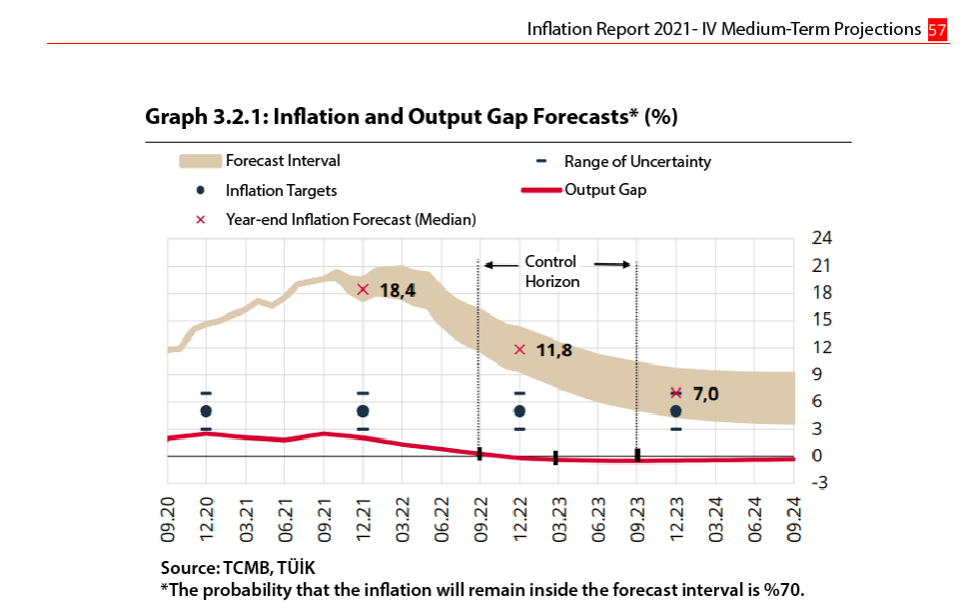

The figure below is taken from Central Bank’s last inflation report in 2021, which was published around the time the government announced the New Economic Model. At that time, the Central Bank predicted that we would end 2022 with an inflation rate of 11.8 percent and the second quarter of 2023 with an inflation rate of around 8 percent. As of April 2023, we are “happy” that inflation has fallen from 85 percent to 44 percent.

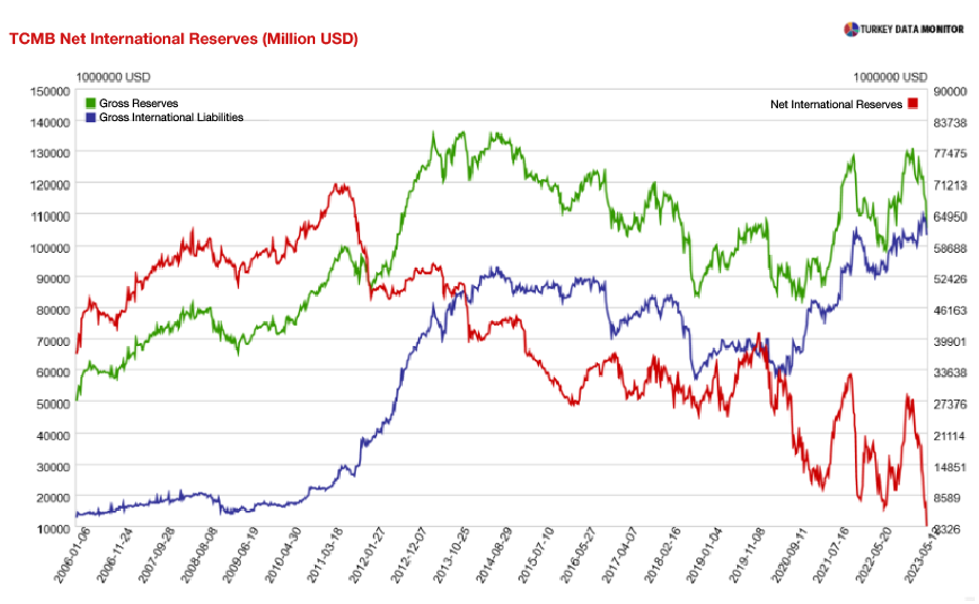

Central Bank reserves at historic lows

The Central Bank’s foreign currency reserves for the week of May 12, released on Friday, reveal the gravity of the situation. The latest figures show that the Central Bank’s net international reserves have fallen to an eye-popping low of $2.3 billion.

The net reserves are the amount that remains after subtracting reserve liabilities from the foreign currency-denominated reserve assets such as bills, bonds, and cash held by the Central Bank. In the week to May 12, the Central Bank’s gross reserves were at $103 billion: In order to provide perspective, it is considered dangerous for gross reserves to fall below a level that would cover short-term debt and the current account deficit. As of May 12, this gap has reached close to $150 billion.

Net international reserves are the most common indicator of a country’s external vulnerabilities. This figure does not include the Central Bank’s short-term borrowings through swaps. When we subtract the swaps, net international reserves fall to -58 billion dollars as of May 12.

What makes this picture even graver is that reserve sales accelerated after the elections on May 14th. Although official figures will be available next week, preliminary estimates suggest that our net reserves are now negative and net reserves excluding swaps are around a historic low of -60 billion dollars.

Heading towards the Egyptian model?

President Erdoğan is adamant that low-interest rate policies will continue. I am worried that this policy path has grave risks for the economy, and if we do not pivot, those risks could manifest themselves very soon. There are countries around where the demand for foreign currency could not be suppressed and the insufficient supply of foreign currency can no longer turn the wheels of the economy. Egypt is one leap forward, and Argentina is three steps forward.

Let’s take a quick look at Egypt: Weak institutions, lack of structural reforms, the decline in investment appetite, flight of foreign capital, and a command economy. The cumulative effects of all these weaknesses materialized rather sharply last year: As a remedy for food inflation exceeding 60 percent, the government advises citizens to eat chicken feet instead of chicken meat to save money.

The last exit before the bridge

The Egyptian pound has lost more than 50 percent of its value against the dollar over this year. It is noted that importers have been unable to withdraw their goods from ports for more than nine months due to foreign currency shortages. Foreign travel has stopped.

Prices of imported goods have skyrocketed. The price of the most ordinary imported food on market shelves has reached jaw-dropping levels. This is what happens when foreign currency gets scarce, and this scenario may not be too far from us.

Turkish economy is going through challenging times. I hope that our policy stance will pivot soon and that the policy makers will steer us away from the bad examples I have presented here. Otherwise, we may find our economy on a rather rough path that is very difficult to reverse, and whose costs will be paid by the future generations.