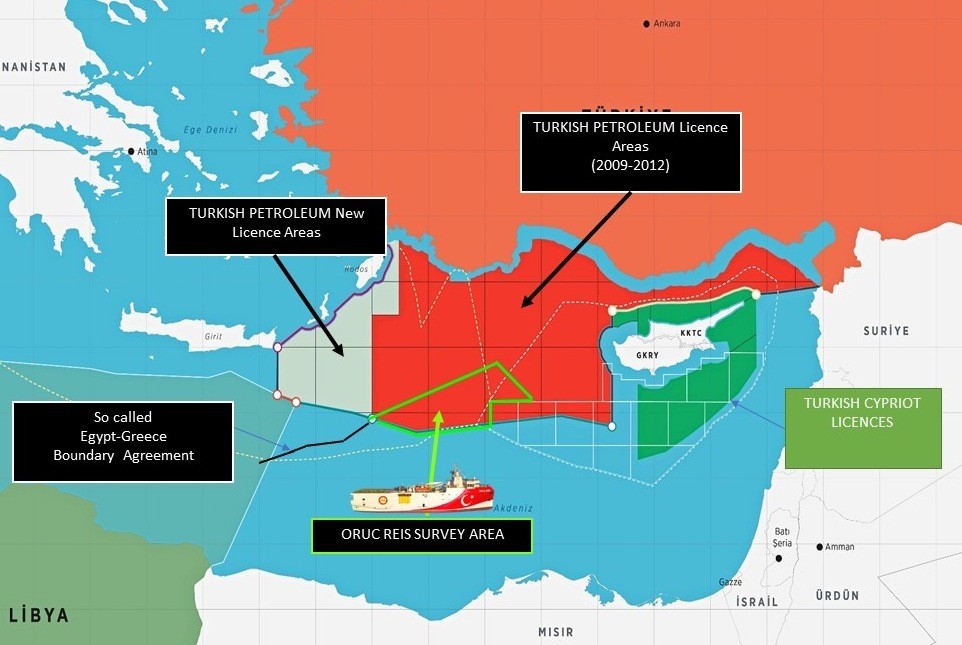

The photo above published yesterday by the Turkish Defense Ministry shows Oruç Reis, the Turkish oil and gas search vehicle, sailing at waters off the southwest of the Cyprus Island, an area declared as an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), both Turkey and Greece.

It is accompanied by five Turkish warships.

The ships from Turkey’s Med Sea port of Antalya on Aug. 10. Simultaneously, Turkey issued a new Navtex, which is basically declaring all civil and military ships that it will be in the region during the given period. The Greek side also took the same step. The Spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Hami Aksoy, explained the reason for the resumption of the search activity, which was previously announced and suspended by President Tayyip Erdoğan upon the “request of Germany and the EU.” Accordingly, Turkey did not receive a positive response to the “goodwill gesture” to give chance to dialogue and Greece signed an EEZ with Egypt on Aug. 6. This agreement contradicts the deal between Turkey and Libya, he said, adding that it “violates the continental shelf.”

Showdown, the quest for dialogue

The Oruç Reis research ship is accompanied not only by Turkish warships (as far as we know, 11 vehicles) but also by warplanes and UAVs.

The situation has freaked nationalist social media users both in Turkey and Greece. When the news spread in the Greek social media that Athens gave Ankara a one-hour deadline (from the night of Aug. 10), messages by the Turkish social media users saying “We are here, where are you?” poured in. Greek social media fighters were trying to instigate their government with insults saying that “10 million lions behind you against 80 million sheep”. The Turkish side responded saying “Ask your grandparents about the cool waters of the Aegean Sea,” with reference to the 1922 Greek defeat in Izmir during the Turkish War of Independence.

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis issued a complaint to NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, accusing Turkey of “provocation” as Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan suggested that all Mediterranean countries should come together for a rightful solution.

The fact that the suggestion comes from the side that made a military move and challenges the other adds a different dimension to the matter. Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuoğlu told the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, in Malta on Aug. 6 that Turkey does not want war, but it would also not let its rights of Turkey and the Turkish Cypriots be violated, he repeated his words on Aug. 11.

Might a war break?

In 1996, Turkey and Greece came to the edge of yet another conflict over the islets of Imia/Imia and were calmed down by the United States. The U.S. interfered because it had paid the price of mistaking that Turkey’s warning over Cyprus in 1974 was bluff. However, the U.S. administration is now focused on its own election issue. The U.S. oil companies have interests in Cyprus and Eastern Mediterranean and the Greek lobby in the U.S. Congress is cooperating with the other anti-Turkey lobbies (including the Israeli, Armenian and Saudi lobbies). France and Turkey are already challenging each other on almost every issue in the Mediterranean from Lebanon to Libya.

As predicted, the Lebanese government resigned on Aug. 10 in the wake of the Aug. 4 explosion in Beirut. The current fragile calm in Libya brought about by the de facto ceasefire can be replaced by conflict again. In Libya, Russia is also on the opposite side with Turkey. Considering the already existing stockpile of weapons in the Eastern Mediterranean due to Syria, it can be seen that a careless spark would enough to trigger an explosion. Meanwhile, Athens is aware that the U.S., the EU and Russia might strongly condemn Turkey in case of a conflict, and even might impose sanctions on Turkey but no one would go to war because Greece wants so.

What is Ankara doing, what is Athens doing?

Athens is bidding to lock up Turkey, the country with the longest coastal strip to the Mediterranean Sea, to its own shores and prevent it from reaching open seas, passing through the self-claimed Greek continental shelf and economic zone. The declaration of a 40,000- square-kilometer jurisdiction area for the 10-square-kilometer island of Castellorizo (Meis) only some 2 kilometers off Turkey’s coastal town of Kaş was the latest straw. And Turkey is trying to show via military diplomacy that it cannot be confined to its own coastal strip, and it will not recognize the Mediterranean agreements that it is not a part of. The Cyprus dispute sits in the middle of this conflict.

When we rewind the developments a little more, we see that the Greek Cypriot Government had declared oil and gas exploration areas without the consent of Turks on the island. In response, the Turkish Cypriot government has granted Turkish Petroleum exploration licenses. In other words, oil and gas exploration was the reason for the struggle for domination in the Eastern Mediterranean, but it is not the main reason. Because the energy resources around the Cyprus island are not enough to make it profitable to extract and sell alone. This is demonstrated by the fact that Greece’s EastMed pipeline project, which was trying to get Egypt and Israel into the business, was in vain after Italy’s withdrawal.

Domestic politics angle

All the disputes between Greece and Turkey so far have benefited the ruling parties in both countries. The same thing might be expected in this instance, too.

Despite the absence of travel restrictions from other EU countries, Greece’s tourism revenues remained low enough for Mitsotakis to publicly complain due to the Covid-19 outbreak, and the Greek economy is in trouble. Another reason for Mitsotakis to avoid a conflict with Turkey is that Erdoğan showed last year that he might broad open border gates for migrants who want to reach Europe whenever it wants. A concerned German Chancellor Angela Merkel wants to remain active on the issue because of this reason. Turkey will probably be high on the agenda at the Berlin meeting of the EU Foreign Ministers on Aug. 27 and 28.

Tension with Greece can also be seen as a side benefit for Erdoğan, who is currently facing problems. The effect of reopening Hagia Sophia for service as a mosque again did not last as long as expected. The propaganda of “teaching Greece a lesson” might divert the focus to this issue from the criticism over an internal crack that emerged due to the economic outlook, the return of the corona outbreak, and women’s rights matters. However, Erdoğan’s proposal for a Mediterranean conference is a sign that Ankara also sees its interests in reconciliation. If Mitsotakis evaluates this, the tension will ease and the possibility of conflict will disappear, and this is what should happen.