Will President Tayyip Erdoğan and Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu’s Jan. 12 meeting with European Ambassadors to Ankara turn into a milestone in EU-Turkey relations? Or will the remarks at that meeting be in vain as the previous ones? Both the course of the developments in Ankara and the talks I had with some of the diplomats attending the meeting, who spoke on condition of anonymity, point to a tendency toward cautious optimism on both sides this time. The EU really wants to believe in Erdoğan. Sure, feelings are mutual. This time Ankara wants to see that the EU is really keeping its promises. Especially because of the severe disappointment in 2004 due to the Cyprus issue and the 2016 agreement hanging in the air.

The optimism has a share in Erdoğan’s softening of his rhetoric, which had blown over the EU, especially France and Greece in mid-2020, as of November. This also played a role in recent steps in line with the expectations of Brussels. The most concrete example of this is the announcement that the “exploratory talks” with Greece, which have not been held since 2016, will resume on Jan. 25.

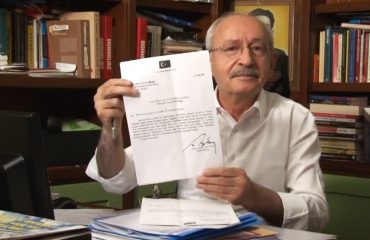

Still, a cautious stance stems from Erdoğan’s increasingly tougher attitude toward his opponents and the press in domestic politics, and the uncertainty about fundamental judicial reform. On Jan. 12, the day when the president reminded the ambassadors of the reforms implemented in cooperation with the main opposition People’s Republican Party (CHP) in 2002 and promised harmony, he sued CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu for 1 million Turkish Liras (roughly $135,000) for naming him as “the so-called president.” He also said he opposed to release of arrested Osman Kavala, a right activist, and Selahattin Demirtaş, former co-chair of Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), despite the fact that this should be a matter of the judiciary. Just a few days ago, he called on citizens not to buy the critical Sözcü newspaper.

By the way, I would like to share an interesting detail. The embassies were notified on Jan. 5 that Erdoğan would also attend the meeting that Çavuşoğlu was scheduled to hold with the ambassadors of EU members. That was the day when Erdoğan went to visit Devlet Bahçeli, the leader of his Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) election partner Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) to talk about reforms discussed at his party’s central decision board (MKYK) the previous day. Interesting coincidence, right? It is known that Bahçeli strongly opposes the release of figures such as Demirtaş and Kavala as part of judicial reform. Erdoğan’s recent meetings as if he is looking for a partner alternative to the MHP add to it. Let’s keep in mind that Presidential Spokesperson İbrahim Kalın refuted the possibility of early elections two days ago that Erdoğan suggested the ambassador a recovery plan for Turkey-EU relations, covering a time span of between 2021 and 2023. Turkey is scheduled to have general elections in 2023.

And let’s go back to the course of developments before the Jan. 12 meeting.

Political shift began with shift in economy

The first change in Erdoğan’s EU discourse began with the U-turn in economic policy that coincided with Joe Biden’s election victory in the U.S. on Nov. 3. Berat Albayrak, his son-in-law, quit his post as Treasury and Finance minister on Nov. 8. Erdoğan finally accepted that the country has run out of its reserves and held his first meeting with the new economy staff on his side on Nov. 11, he met with the representatives of foreign capital (International Investors Association – YASED). On Nov. 13, he said for the first time that Turkey has to go through “a new period of reform in judiciary and economy.”

“We envision our future with Europe,” he said on Nov. 21, surprising everyone.

Another turning point was his statement on Dec. 11, 2020, that came after the EU announced that it delayed its decisions about Turkey, which was basically for consulting Biden on the issue after he takes the helm in the U.S.

On Dec. 16, Kalın held a video conference with the EU Ambassadors in Ankara. On Dec. 18, the EU’s representative in foreign and security policy, Josep Borrell, wrote on an EU blog that “Turkey has become a regional power to be reckoned” and “It is clear that the European Union will not be able to achieve stability on the continent unless it finds the right balance in its relations with Turkey.”

Acceleration in diplomatic contacts

Turkish Foreign Minister Çavuşoğlu’s visit to Spain on Jan. 8 was important. Recently, Spain has been standing close to Ankara in the easter Mediterranean issue, just like Italy.

On Jan 9, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen had a talk with Erdoğan on putting relations on a new track through mutual steps. Erdoğan recalled that the EU should its promises in the 2016 agreement on migrant inflow. Von der Leyen reminded that tensions in the eastern Mediterranean issue should not escalate and they expect judicial reform from Turkey.

Borrell invited Çavuşoğlu to Brussels on Jan. 10, the foreign minister is expected to be in the city on Jan. 21.

On Jan. 11, Turkish Cypriot Foreign Minister Tahsin Ertuğruloğlu was in Ankara for the “Eastern Mediterranean Conference” and he met with everyone, including Erdoğan. On the same day, the issue of reforms was discussed in the cabinet.

And came the Jan. 12 meeting with the ambassadors of the EU members. Meanwhile, Erdoğan announced that von der Leyen and European Council head Charles Michel would visit Turkey in late July. He also announced the 2021-2023 National Action Plan for EU. Turkey’s accession would be an “ontological” preference for the EU, he said.

Judiciary reform a tough challenge

The impression I got from the EU ambassador I have talked to is that they evaluate relations with Turkey under three main headlines.

The first is the political steps I just tried to convey above. (It was meaningful that one diplomat said “We understand that there can be no resolution in the eastern Mediterranean without Turkey’s contribution)

The second headline is about economic steps that need to structural and not limited to temporary measures. They consider this issue both in terms of European investments and Turkey’s economic stability. The third is that the judicial reform would not remain in words but turns into concrete steps.

This third issue is the most challenging of all for Erdogan. A diplomat summed up the situation: “We have gotten good signs of the first two, but there is no step for the third one yet.” Bahçeli plays a restraining role here. It may not be easy to convince Bahçeli, who favors the restoration of the death penalty and the closure of the HDP, to reforms. Or maybe this time, Erdoğan will take the “bitter pill” even though he cannot convince Bahçeli, and say that “There is nothing we can do about it.”

It would be nice if both the EU and Turkey keep their promises this time and this would ease Turkey’s issues of democratic rights, freedom of the press, high cost of living and unemployment. Otherwise, it can turn into yet another disappointment.