Turkey registered a 1.8 percent growth rate for 2020 and became one of the few countries that achieved positive growth during the pandemic. The growth performance was primarily a consequence of the excessive credit growth and low interest rate policies adopted during 2020. Yet, the consequent pressures on the TL and the sale of central bank reserves to offset such pressures generated further vulnerabilities that are inherited in 2021. The economic outlook will be shaped by how such vulnerabilities are addressed in the road ahead. The low interest rate policies that gave rise to positive growth were not sustainable. After reaching a peak of 8.46 TL per Dollar in early November, Turkish Lira appreciated 17 percent in three months, following the replacement of the team in charge of economic policies. For an economy where the external borrowing of the private sector is more than 30 percent of the GDP, this is a huge relief. Nevertheless, we are not out of the woods yet. Turkey is still walking a tightrope between a tight monetary stance to stabilize the inflationary pressures, and entertaining the idea of a more accommodative policy stance to support the economy.

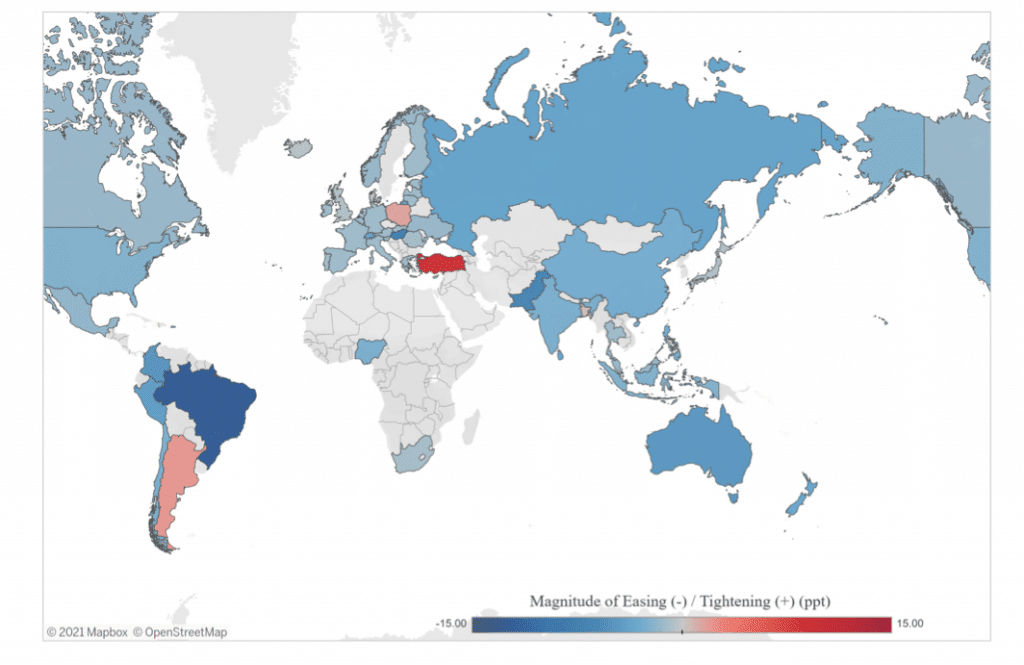

Turkey is one of a handful of countries that tightened its interest rate during the pandemic while almost the entire world eased rates to offset the drag of the pandemic. There are three questions that one can ask:

1. Why did Turkey raise interest rates in the middle of the pandemic?

Turkey had to raise interest rates due to previous negligence on price stability. Inflation targeting has never been a priority in Turkey, despite the fact that explicit inflation targeting was adopted in 2006. One can view price stability as a “gift” that comes in handy during times of recessions. This is because a low and stable inflation rate allows the central bank to cut the policy rate and support the economy without triggering inflationary expectations. Unfortunately, we did not have that gift. On the contrary, the inflation rate was at 12 percent when the pandemic hit Turkey in March 2020. Instead of a carefully communicated monetary easing to offset the economic slowdown, Turkey adopted a poorly communicated and unorthodox policy stance. Policy rate was cut significantly below the inflation rate and the consequent sell-off in Lira was offset by selling foreign exchange reserves.

When there was simply no more room to manuevour and central bank’s net reserves turned significantly negative, the economic team was replaced. The new team had no choice but to hike interest rates to stop the flee. Financial markets have stabilized since then.

2. Why did the market rates actually decline following the rate hike?

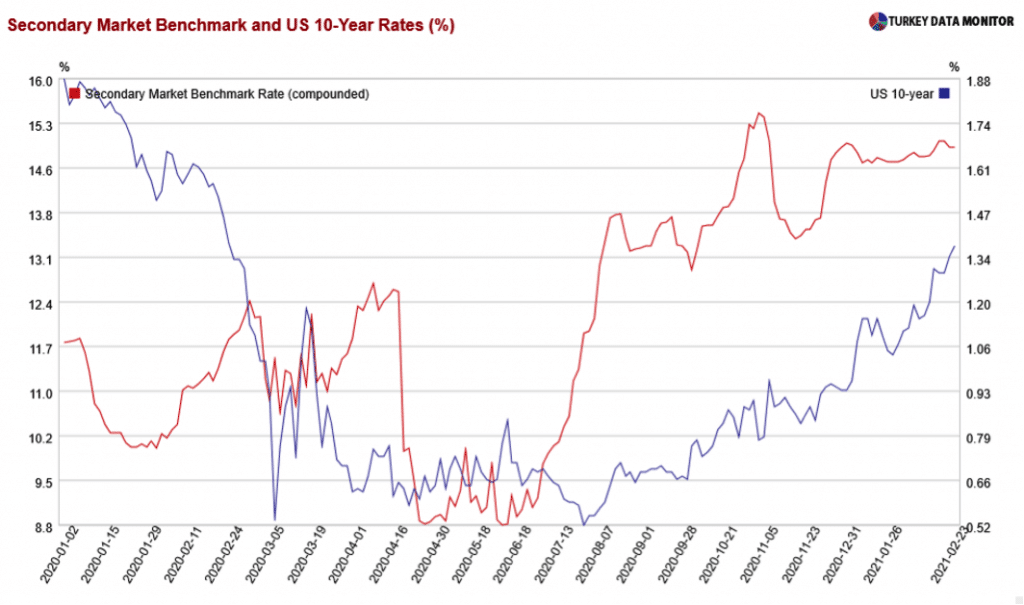

Long-term interest rates in Turkey are determined by the country risk, inflation expectations, US bond rates, and policy rate among other factors. When the central bank switched to a tighter policy stance, the markets were relieved. Defending the TL through the policy rate and abondoning the replenishment of central bank reserves was an orthodox move that was inevitable. It addressed the key macroeconomic vulnerabilities. The consequent decline in the risk premium and inflation expectations led to almost a 2 percent decline in market rates in November, despite the fact that Central Bank had increased the policy rate by 4.75 percent in that month. The rate hike led to an easing in financial markets, consistent with what the literature calls an “expansionary contraction.”

3. Why are we still not out of the woods yet?

A close look at the figure reflects the timid trend of the benchmark interest rate in Turkey (red line, the left axis). It is true that the switch to orthodox policies in November provided the much-needed relief and eased the tension in financial markets. However, the long-term interest rates have been following an upwards trend since then. The trend is partly due to the increase in the 10-year interest rates in the US (blue line, the right axis). The combined effect of President Biden’s 1.9 trillon USD stimulus package and the vaccination rollout led to an increase in inflation expectations in the US, which is reflected in long-term interest rates.

Another reason for the upwards trend could be the overall skepticism regarding the sustainability of the current policy stance. Although central bank governor Naci Ağbal and the minister of Treasury Lutfu Elvan have been in great harmony so far, the markets are still worried. Market jitters are particularly pronounced when there are political commentaries that praise the former economic team or favor rate cuts. Our recent research illustrates that TL exhibits a significant response to such political commentaries, reflecting the markets’ belief that the CBRT will accommodate such pressures. A more muted response is observed in Hungary and New Zealand where political commentaries that ask for rate cuts increase exchange rate volatility. Our findings imply that the effect of political pressures tends to be accelerated in environments where economic fundamentals and institutions are weaker.