In the last days of April, two important developments took place in the Turkish defense industry. First, on April 22, Akıncı drone, which is being developed by Baykar Savunma fired precision-guided munitions for the first time. The prototype aircraft, designated PT-3, achieved accurate hits by three different types of guided bombs, MAM-C, MAM-L and MAM-T, all manufactured by ROKETSAN. The second development was announced by President of Presidency of Defence Industries (Savunma Sanayii Başkanlığı; SSB) Prof. Dr. İsmail Demir two days later. Demir revealed that the Aksungur drone developed by Turkish Aerospace (TAI) released a long range precision guided bomb designated Kanat Güdüm Kiti (KGK; wing guidance kit).

Both Akinci and Aksungur projects are in development and testing phase and they are expected to enter service shortly. Both drones are capable of flying longer durations, carrying more payload and weapons, compared to their predecessors Anka and Bayraktar TB2, therefore their introduction to service mean Turkey entering a new league of drones.

Turkey had already attracted the attention of the world with its works and activities in this domain. Especially since the beginning of 2020, the performance, and effects of Turkish-made drones in Syria – Idlib, Libya, Eastern Mediterranean and most recently in Nagorno-Karabakh, are subject of intensive examination and discussion in international defense and security circles. Most recently, the renowned political scientist Francis Fukuyama also contributed to these discussions with his article published on the American Purpose website on April 5. Fukuyama wrote that Turkish drones changed the nature of war and played an important role in Turkey’s claim to become a regional power.

Rules of the game changed?

Did armed drones really change the rules of the “game”? It is difficult to give an exact “yes” answer to this question. However, it seems possible for armed drones to trigger some important changes.

First of all, it is necessary to take a look at the use of armed drones in the above mentioned conflicts. In all of these fields, armed drones were used in coordination with other elements, especially electronic warfare, and artillery assets. Especially in Idlib, Turkey, taking advantage of the proximity of the operation area to its own territory, deployed drones in coordination with electronic intelligence, electronic warfare, combat aircraft and artillery units. Drones were used both in reconnaissance, surveillance, and intelligence missions with onboard electro-optical cameras, and they hit the targets they detected. Throughout these reconnaissance – strike operations, armed drones flew under the protection of electronic warfare systems. The use of armed drones in this way was unprecedented until then: The United States uses Predator and Reaper drones almost exclusively for striking high value targets and assassination type missions.

Secondly, in cases where the enemy air defenses were disabled or not operable, armed drones were observed to be extremely effective against targets such as artillery, armored units, and fixed positions. A drone carrying 2-4 guided bombs is capable of striking several targets in one sortie also had the potential to serve as a psychological warfare asset through the publication in social media of the footage showing targets being eliminated. Azerbaijan has made good use of this advantage during the Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Balance of cost and performance

In addition to the deployment in coordination with other assets, another innovation brought by Turkey compared to the U.S. or Israel is to achieve a fine balance between cost and performance. Thanks to its relatively low cost, a large number of Bayraktar TB2 drones (as much as around 100 according to open sources) has entered service. The drone has exceptional flight performance and is equipped with advanced cameras as well as ability to carry low cost, miniature precision guided munitions. Although a number of TB2’s were shot down in Idlib and Libya, these were replaced very easily and quickly. Furthermore, Turkey was able to fly several TB2’s simultaneously, greatly increasing intelligence gathering capabilities and concentration of firepower.

Despite these benefits and advantages, some important military and technical shortfalls of drones remain. First of all, the survivability of drones is not high against a well-equipped and organized air defense and electronic warfare capability. Although Turkish armed drones inflicted significant damage on enemy air defense systems in Idlib and Libya, Turkish drone fleet also suffered some losses during this time. It is extremely difficult for drones which fly at relatively low speeds and have low maneuverability, to be effective without the protection of established air superiority and cover of electronic warfare. For this reason, the claims that drones have ended the era of tanks or piloted comabt aircraft do not seem realistic.

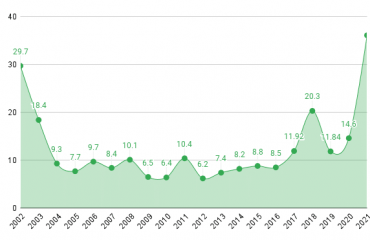

As for the role of armed drones playing significant role in Turkey’s claim to become a regional power, it seems that this issue has two dimensions. The first is that Turkey effectively uses drones in its military activities within and beyond its borders. We have seen the most obvious example of this in Syria and Libya. The second is the development of military-technical cooperation with the export of drones, and therefore the use of the defense industry as a foreign policy instrument: Turkey has exported Bayraktar TB2 and Anka drones to Qatar, Ukraine, Libya, Azerbaijan and most recently to Tunisia. These sales play important roles to strengthen military-strategic relations with the buyer countries. It can be said that such export moves are important reflections of the security-oriented foreign policy followed by Turkey in recent years.

Finally, it is necessary to highlight an important change brought to the agenda by armed drones in international security. As a result of advances in technology, it has become easier and cheaper to manufacture unmanned vehicles, and it has become easier to use such platforms. This made it possible for many countries to produce or buy armed or unarmed drones. In the early 2000s, very few countries were able to produce and sell drones. However, now even terrorist organizations can produce bomb-laden drones in small workshops. The risk that this transformation brings to the agenda with the performances of armed drones in recent conflicts is that countries with modest resources can pursue more aggressive foreign policies or be more assertive to resolve disputes through conflicts. In other words, the widespread use of armed drones can dangerously lower the threshold of start of armed conflicts.