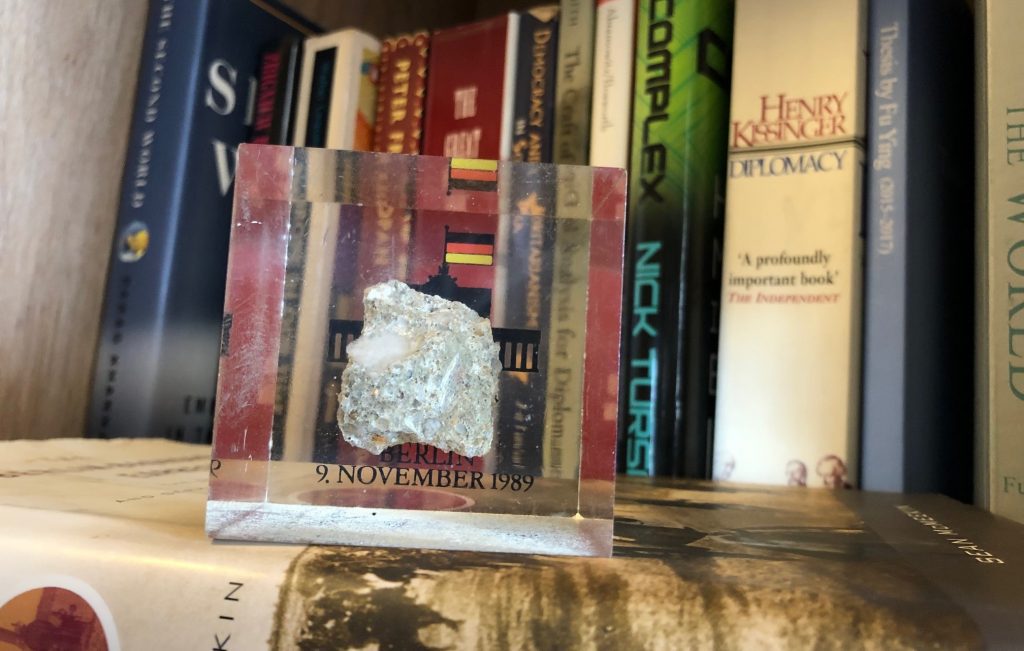

The 20th century started drawing to a close with the fall of the Berlin Wall. Television screens, advertisements, and posters were full of symbolic representations of this historic moment. Yet listening to commentary from the 1990s, from the vantage point of three decades later, one can see just how mistaken the pundits were in their predictions regarding the post-1989 era. Once walls and borders had been torn down – so the argument ran – freedom would immediately rush in. Perhaps this optimism was inevitable.

Thus, while stones from the Berlin Wall were being sold in gift shops, the Western world was busy proclaiming the “End of History“. The phrase refers to the eponymous bestseller by Francis Fukuyama, a scholar widely fêted at the time. Fukuyama maintained that humanity’s ideological evolution was essentially complete and that Western-style capitalism and liberal democracy would now enjoy unchallenged currency as a model of how to run a society. Capitalism seemed endowed with almost magical powers, bringing about the End of History as effortlessly as it turned pieces of the Berlin Wall into consumer goods.

The changes globalization has wrought upon our lives are indeed astounding. We wear shirts made for pennies in Bangladeshi sweatshops and eat Peruvian quinoa as part of the latest fad diet; the Starbucks on the corner offers a vast array of coffees grown everywhere from Sumatra to Kenya. Nearly every corner of the globe has become a tourist destination – at least for those who can afford it. Online shopping, online banking, online education, online fatwas: countless aspects of our daily lives have entered the virtual realm. New wars, new weapons, new enemies, new forms of terrorism and other threats, and new disasters are constantly on the horizon.

We are surrounded everywhere by the virtual, the hybrid, the automated. With few remaining curbs on the flow of capital, goods, and information, this final stage of capitalism known as globalization has profoundly altered economic, social, and political relations, turning our planet into one big marketplace.

From the Wuhan Animal Market to the Global Market

Entry into today’s global market inevitably means doing business with China. The offspring of an authoritarian communist political system and a capitalist economic system, China is a living refutation of the “End of History” thesis. With exports totaling 2.5 trillion dollars (or 13.5{4a62a0b61d095f9fa64ff0aeb2e5f07472fcd403e64dbe9b2a0b309ae33c1dfd} of total global exports), it has a trillion dollar-a-year lead over the quintessential capitalist liberal democracies, the USA and Germany, with their roughly 1.5 trillion dollars’ worth of exports each. The authoritarian regime in Beijing, which can manage its own capitalist system more efficiently and profitably than liberal democracies, is undoubtedly one of the reasons for the Chinese economic miracle. Today, Chinese-made products – everything from toys to smartphones – are ubiquitous.

Just a few months ago, few people outside of China had heard of the city of Wuhan. It was there, at a live animal market, that Coronavirus (COVID-19) is believed to have been first transmitted from a bat to human beings. At the time of writing, the virus has spread to even the most remote island-nations. Killing thousands of people daily, Coronavirus has become the most serious pandemic in living memory, bringing social and economic life around the globe to a complete halt.

Before the outbreak, six million people boarded an airplane every day; now hundreds of millions are effectively housebound. Great metropolises like New York, London, Istanbul, Milan, and Paris, the crossroads of the global economy, have become eerily silent, as in a disaster film. The EU, which has long boasted of “doing away with borders,” has even closed its internal borders between member states. People’s daily lives are severely curtailed by isolation and quarantine orders, travel restrictions, and curfews.

Tearing Down Walls – and Building Them

The present crisis of liberal democracy and capitalism (it would be premature to call it a divorce) has witnessed symptoms like the rise of the far-right, anti-migrant and other xenophobic sentiments, Brexit, and the Trump presidency, which has shaken the American political establishment to the core. None less than Fukuyama himself has publicly stated that “Socialism ought to come back”. In this remark, which has been widely quoted by the left-wing media, Fukuyama was referring not to Soviet-style socialism, with its public ownership of the means of production, but to Scandinavian social democracies, which strive for a more just, equal distribution of income and prosperity.

Revolting against the conditions brought about by inequities in global wealth distribution, the world’s poor are knocking on the doors of wealthy Europe. Some go over land in search of a better life, while others risk drowning as they cross the Mediterranean and Aegean in boats via Italy, Spain, and Turkey. It would be hard to find a more tragic illustration of the consequences of globalization.

The situation in the US is equally chaotic. At the heart of American iconography is an effort to globalize America’s brand and American values. The iconoclastic US president Trump, by contrast, campaigned on promises of limiting free trade and rebuilding the economic “walls” provided by tariffs. Trump has pandered to xenophobes, insisting on referring to the Coronavirus pandemic as the “Chinese virus”; in a March 23 tweet, he explicitly linked the Coronavirus threat to his own economic protectionism, exclaiming, “This is why we need borders!”

So, it seems that three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we are returning to an era of walls and borders. A little over thirty years ago, US president Ronald Reagan visited West Berlin. Speaking before a crowd in front of the Berlin Wall he addressed Moscow in the following words: “General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, open this gate…Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” Today, we have an American president who believes that the US should seek prosperity by building a wall against its neighbor, Mexico, and that he will be able to stop a virus by fortifying his nation’s borders.

The End of Geography?

Borders are inherently self-perpetuating. That is, individuals and societies not only shape the borders within which they live but also have their own identities shaped through a sense of attachment to a specific region. Every political and economic system of power must use borders to demarcate the geographical region in which people live; a state not defined by a specific geographical location is inconceivable. The raison d’être of any state is the ability to decide where a border will be drawn, who will remain inside, and who will be left outside. Borders serve to create unity and integrity by means of shared similarities and to decide what differences will be tolerated (or not). They reinforce a sense of ownership and identity with respect to what lies inside them, as well as a sense of being protected against what lies outside.

Of course, it is not only states that draw borders. Both within and without the nation-state, numerous entities such as neighborhoods, gated communities, gangs, terrorist organizations, religious communities, and global firms use borders to organize, provide security, control circulation or distribute resources. For all actors – whether the nation-state or the smaller-scale ones listed above – that use borders in their struggle for dominance are simply parts of a whole that has been divided and partitioned. No matter how much borders are reinforced, absolute isolation is impossible, for all borders are permeable. Circulation, fluidity, and interaction can be reduced but not completely eliminated.

Thus, in today’s world, the claim that globalization would abolish all borders and bring about the “End of Geography” has proven to be just as groundless as the “End of History” thesis. As Coronavirus spreads across the globe, societies are having recourse to a simple, age-old solution: closing their borders. For a brief period, this may act as a palliative measure; however, in an integrated, inter-dependent world like our own, such a solution is unsustainable. Trump, with his cries for “borders, borders,” does not lift a finger when it comes to global warming.

Meanwhile, industrialized nations such as China keeps exacerbating the problem of carbon emissions. In such circumstances, who will be able to prevent the migration of millions of new climate refugees, once their agricultural lands have been turned into deserts, their sources of fresh water have dried up, and poverty has left them no alternative but to flee? Climate change is slowly but surely leading us towards disaster. What wall or border will be able to accomplish what the Great Wall of China and the Berlin Wall could not?

Societies will continue to draw geographical borders on the local, regional, and national levels. A homogenous, uniform world, ruled by a single world government, does not seem possible in the foreseeable future. But this does not mean that we can solve our current problems by closing our borders. Instead of remaining fixated on individual states – and inter-state conflicts – as the solution to our problems, societies must accept their differences and find ways to work in solidarity with one another. Otherwise, the climate crisis, infectious diseases, drought, and the unequal distribution of global income will have horrendous consequences for us all. And there is no wall high enough to protect us from such a catastrophe.