The real tremors and transformation pain of the People’s Alliance intensify on the ideological ground, the identity problem.

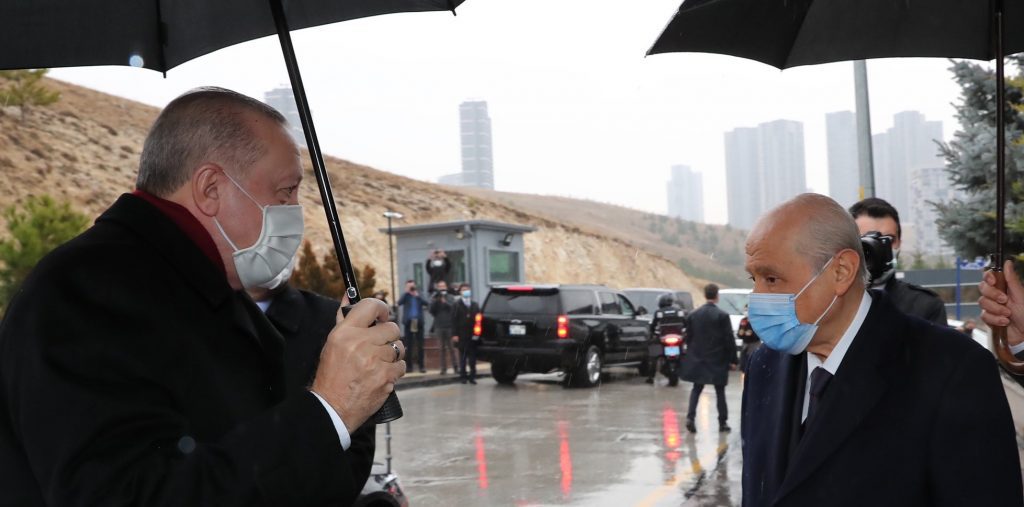

Both Justice and Development Party (AKP) leader President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his election partner Develt Bahçeli, the head of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), do not miss a chance to highlight that their People’s Alliance is standing firmly. They repeat their confidence that the alliance will win the 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections.

However, looking at a series of developments by the last months of 2020, one can see that things within the People’s Alliance are not as comfortable as in the 2018 elections, for example, or the 2019 elections.

This discomfort partly stems from international developments. Joe Biden today moves to White House today in the shadow of soldiers and we will discuss the increasing pressure on Turkey and Erdoğan during his tenure. But there are also domestic reasons for such discomfort. It is not a bottleneck caused only by economic troubles, it has rather political and ideological aspects. An “identity” problem seems to have arisen in the People’s Alliance.

From Erdoğan to Erbakan, From Bahçeli to Türkeş

Erdoğan’s love for Milli Görüş, his political roots that roughly translated into English as “National Vision” has relapsed in recent weeks. On Jan. 6, he met with Oğuzhan Asiltürk, a senior figure of Saadet Party, an offshoot of the Milli Görüş movement, and the next day with party senior Oğuzhan Asiltürk. On Jan. 19 he visited the grave of Necmettin Erbakan, his political tutor. These visits and photographs were published by the Presidency’s Directorate of Communications.

One day before meeting with Karamollaoğlu, Erdoğan visited Bahçeli, at his home on Jan. 5 for the third time in a week. It was announced that reforms were discussed. Bahçeli’s objections to the scope of the judicial reform were known. When AKP senior Bülent Arınç spoke about the release of Selahattin Demirtaş and Osman Kavala, he was left out by upon pressure of Bahçeli.

Erdoğan’s renewed emphasis on the National Vision roots at the time when he was looking for a basis for reconciliation with the EU –mainly for economic reasons– could also balance the discomfort felt inside the AKP against the MHP acting like a ruling partner. Bahçeli also had his moves against Erdoğan embracing Erbakan’s legacy. He started to highlight the nationalist legacy of Alparslan Türkeş.

Grey Wolves campaign on social media

The tag #ÜlküOcakları (the nationalist Grey Wolves ) was opened on social media after Bahçeli’s move on Jan. 14. Bahçeli targeted some journalists on Jan.14, because they argued that the MHP was pushing the AKP to shut down the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).

At the same time, he published “14 Demands”, which did not attract much attention. Among these demands, there were articles ranging from the conditions of changing elections law and political parties to the blocking of the HDP and the control of political polls. Bahçeli published these demands after Erdogan pledged reform to EU Ambassadors in Ankara on Jan. 12. The president was the addressee of Bahçeli’s demands. On the same day, politician Selçuk Özdağ, the Vice President of the Future Party, and şAnkara Representative of Yeniçağ Newspaper Orhan Ugüroğlu were attacked. The day before, Ugüroğlu published an interview in which Özdağ, a politician with grey wolves origin, had criticized Bahçeli.

On Jan. 18, Bahçeli targeted Taha Akyol, who interviewed Future Party Ahmet Davutoğlu who held Erdoğan responsible for the attacks and warned that Erdoğan “would be liquidated” by the supporters of the Feb 28, 1997 ‘”post-modern coup.” Akyol was in the MHP administration before the Sept. 12, 1980, military coup.

Bahçeli’s problem: nationalists outside the MHP

Journalists Ahmet Takan, Yavuz Selim Demirağ and Sabahattin Önkibar, who were injured in similar attacks before, also came from grey wolf roots.

Was it meant to show what would happen to those who left the ranks?

The #ÜlküOcakları tag was opened at a time when some EU countries were in action to name the Grey Wolves illegal. Under the tag, videos showing Bahçeli emphasizing that the Grey Wolves, the MHP’s youth organization, is the “legacy” of the party’s late founding leader, Alparslan Türkeş. An effort to prevent the MHP identity from “mixing” with the AKP or other identities is also observed.

As long as the Good Party, which was founded by those who broke with the MHP to a large extent, remained within the Nation’s Alliance with the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), it would not be that much problem for Bahçeli. But the fact that comments seeing İYİ Party leader Meral Akşener could replace Bahçeli as an ally for the AKP started to appear on media outlets in line with the AKP changes the situation. Moreover, some former MHP or Grey Wolves figures are today seen within the Future Party, Deva Party, Democrat Party and even the CHP. For example, Mansur Yavaş was elected Ankara mayor from CHP.

Turkeş and “furious nationalism”

In fact, the divisions had begun when Tuğrul Türkeş, the son of MHP founder Türkeş, moved to the AKP at a time when Bahçeli was strongly criticizing Erdoğan. Türkeş showed to the base of the MHP that cooperation with the AK Party can be effective in the state administration, and that things can be done for the benefit of Grey Wolves at state offices or municipalities. Bahçeli’s change of course toward the People’s Alliance came because he saw the rise of the HDP in the June 7, 2015 elections ahead of before the 15 July 2016 military coup attempt and set a goal to take part in the state administration, launching a presidential system debate with Erdoğan. Tuğrul Türkeş played an important role in that period.

Türkeş later published an article, which was apparently written before the recent attacks, but he admitted that “coincided well”. The article was headlined “Furious nationalism: On the developments in the world and Turkey in the first quarter of the 21st century. ” In his article, Türkeş introduced concepts of “bad nationalism” and “furious nationalism” along with “good nationalism.” According to him, Turkey’s founding father was an example of “good nationalism” as Adolf Hitler was an example for “furious one.”

“Unfortunately, I see a risk that such type of rhetoric-based nationalism may be close to getting rooted in the sociological grassroots.”

The real tremors are on the ideological ground

Tuğrul Türkeş also makes the following statement on “furious nationalism”: “It is not possible to even catch the era -not speaking of leading it- for such formation that is completely hollow, unplanned and therefore far from maturity to respond to the ‘Call of the of History.'”

This definition is similar to the approach that Meral Akşener criticizes, “the lumpen nationalism”.

The call of the history mentioned by Türkeş is the wind of change and transformation that the world faced at the beginning of the 21st century. It seems that the unavoidable rise of China, and then the Covid-19 pandemic brought humanity to a new corner in the course of history. The tremors experienced by the U.S., the world’s largest economic and military power, are a clear indication of this.

Joe Biden’s administration will be a test not only for the U.S. but also for the international political and economic system. Transformation and change seem inevitable. It will inevitably affect Turkey and the People’s Alliance that rules it.

It is no coincidence that Erdoğan started to highlight the National Vision and the EU tendency, and Bahçeli the rhetorical nationalism trend in such a period. The real tremors and transformation pain of the People’s Alliance intensify on the ideological ground, the identity problem.