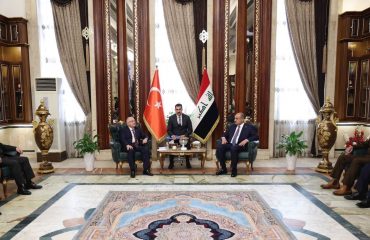

After Ekrem İmamoğlu’s imprisonment, Turkish opposition CHP leader Özgür Özel also faces a prison threat, and he is not the only political leader under the threat of imprisonment. Özel is in the upper left corner as he was observing one of İmamoğlu’s trials.

In Turkish politics, the threat of imprisonment has reached CHP leader Özgür Özel. Presidential decrees have been sent to the Turkish Grand National Assembly (TBMM) to lift the parliamentary immunity of Özel and CHP İzmir MP Tuncay Özkan for trial. The reason is their accusation of the Court of Appeals members of staging a “coup against the Constitutional Court”, thus “insulting a public official”, who refused to comply with the Constitutional Court’s ruling in favor of Can Atalay, a Turkish Labor Party (TİP) MP elected in the 2023 elections despite his finalized prison sentence from the Gezi Park protests in 2013. Under the Turkish Penal Code, this offense against Özel carries a penalty of one to two years in prison.

Immunity can be lifted in the TBMM with a quorum, ie, 151 votes, meaning it could be done with AK Party votes alone. This is not the first request to lift Özel’s immunity. When asked about it in İzmir, where he went due to the detention of former İzmir Mayor Tunç Soyer, Özel responded, “If we were afraid of iron, we wouldn’t ride the train.”

Rivals under threat of imprisonment

Özel is not the only political leader awaiting a vote in the TBMM to lift immunity. Kurdish-problem-focused DEM Party Co-Chairs Tülay Hatimoğulları Oruç and Tuncer Bakırhan, as well as center-right İYİ Party leader Müsavat Dervişoğlu, are also on the list. Despite currently good relations between the DEM Party and the ruling AK Party-MHP alliance due to discussions around the PKK laying down arms or a “Terror-Free Turkey” process, this should not mislead anyone. During the 2012-2015 period, relations with the DEM Party’s predecessor, HDP, also seemed positive. However, when that process ended, PKK resumed its terror actions, the immunities of HDP co-chairs Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ were lifted, they were sentenced to prison, and they remain incarcerated. (It’s worth recalling CHP’s strategic mistake in supporting the lifting of immunities in 2016, which led to CHP İstanbul MP Enis Berberoğlu being the first to receive a prison sentence.)

Currently, the leaders of three of the top five parties in the TBMM—political rivals of the AK Party government—are under the threat of imprisonment. Zafer Party leader Ümit Özdağ, who lacks parliamentary immunity as he is not an MP, has recently been released from Silivri Prison.

İmamoğlu is already in prison

Ekrem İmamoğlu, the İstanbul Metropolitan Municipality Mayor and CHP’s declared candidate for the next presidential election, has been in prison since March 19, 2025. He faces multiple cases that could lead to prison sentences and political bans.

However, the İstanbul Chief Reublic Prosecutor’s Office has yet to disclose the indictment regarding his arrest on corruption charges, despite over 100 days having passed. Instead of an indictment, claims based mostly on statements from informants, which should legally remain confidential during the investigation, are being spread by pro-government media and the publicly funded broadcaster TRT.

This tactic has been used in Turkey during periods of societal suppression, with recent examples including the radical military faction during the February 28, 1997 campaigns against the government of the time and by the Gülenists during the Ergenekon-Balyoz trials of 2008-2012.

To reiterate, there is still no indictment. If one were released, the results of investigations overseen by Chief Prosecutor Akın Gürlek would be made public and open to free discussion. There is also unease among both opposition and some ruling party MPs in the TBMM regarding the delay in the indictment.

Informants are the latest excuse

The delay in the indictment has caught the attention of pro-government media, as seen in Mahmut Övür’s column in the Sabah newspaper. Övür doesn’t explicitly ask, “Why is there still no indictment?” He writes that informants against İmamoğlu seem to say a lot but reveal nothing substantial about the alleged crimes, suggesting this is orchestrated by İmamoğlu and resembles Gülenist tactics. Övür also questions why many informants are in hospitals, dismissing the possibility of genuine illness and tying it to İmamoğlu’s alleged scheme, essentially warning prosecutors they are being “played.”

The political landscape shows that many leaders and key figures of the AK Party government’s political rivals are under the threat of imprisonment. İmamoğlu, who has announced his candidacy against President Tayyip Erdoğan, is already in prison, beyond mere threats.

The foundation of a pluralistic democracy and the rule of law relies not only on the separation of the judiciary, legislature, and executive but also on free political competition, an independent judiciary, and a free press.

The fire does not only burn where it falls; it spreads everywhere.